...no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or

affirmation, and particularly describing

the place to be searched, and the

persons or things to be seized." Fourth Amendment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

a. Was there a nexus between the evidence, place of

search, and time of search at the time warrant issued?

|

|

|

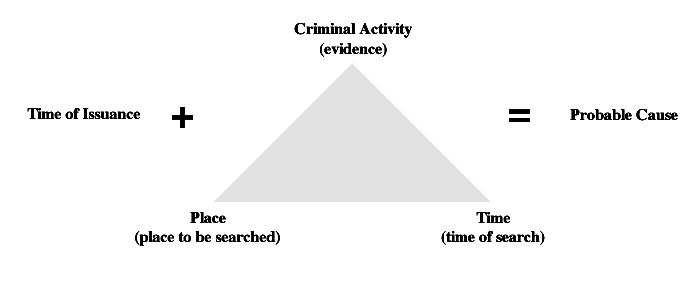

Probable cause requires a nexus between the items to be seized and the

place to be searched. That nexus must exist at the time the warrant

issues. [Probable cause] is

established if, when the warrant issues, the magistrate has information that

would cause a reasonably prudent person to believe that the items to be seized

will probably be found in the place to be searched at the time the search is

conducted. Thus, the question here is whether the Lewis County magistrate, at

the time he issued the warrant, had probable cause to believe that contraband

would be present in Goble's house when the warrant was served.

State

v. Goble, 88 Wn.App. 503, 511 (1997).

If at the time of issuance of the warrant there is reason to believe that

evidence of criminal activity will be found at the place to be searched at the

time of search, then there is probable cause for the search.

(what, when, where)

To be sufficient, an affidavit in support of a search warrant must “recite

specific data as to times, places and magnitude of previous criminal activity.”

State v. Higby, 26 Wn.App. 457, 463 (1980).

Specific Nexus Issues

Multiple-occupancy units

A search warrant for a multiple-occupancy building will usually be held invalid

if it fails to describe the particular subunit to be searched with sufficient

definiteness to preclude a search of one or more subunits indiscriminatel State

v. Alexander 41 Wn.App 152, 153-54 (1985).

Probable cause at time of issuance.

It is not enough, however, to set forth that criminal activity occurred at some

prior time. The facts or circumstances must support the reasonable probability

that the criminal activity was occurring at or about the time the warrant was

issued. Tabulation of the intervening number of days is not the final

determinant of probable cause, but is only one factor considered along with all

the other circumstances including the nature and scope of the suspected criminal

activity.

State v. Higby, 26 Wash.App. 457, 460-61 (1980) (citations

omitted.)

Obviously, there may be probable cause to search for and seize one item but not

another. A typical example is the police requesting and the warrant granting

authorization to search for records of drug sales when there is evidence of

possession but not of dealing.

|

|

|

b. Is there an Augilar-Spinelli

issue relating

to evidence based on informant statements?

|

|

|

To satisfy both parts of the Aguilar-Spinelli test, a magistrate must require an

affidavit to state underlying circumstances which the magistrate may draw upon

to conclude the informant was credible and obtained the information in a

reliable manner. If either or both parts of the Aguilar-Spinelli test are

deficient, probable cause may yet be satisfied by independent police

investigation corroborating the informant's tip to the extent it cures the

deficiency. The knowledge part is satisfied by a showing that the information

provided by the informant was based upon personal knowledge.

State v. Vickers, 148 Wn.2d 91, 111 (2002).

The two prongs of the Aguilar-Spinelli test have an independent status; they are

analytically severable and each insures the validity of the information. The

officer's oath that the informant has often furnished reliable information in

the past establishes general trustworthiness. While this is important, it is

still necessary that the “basis of knowledge” prong be satisfied-the officer

must explain how the informant claims to have come by the information in this

case. The converse is also true. Even if the informant states how he obtained

the information which led him to conclude that contraband is located in a

certain building, it is still necessary to establish the informant's

credibility.

The most common way to satisfy the “veracity” prong is to evaluate the

informant's “track record”, i.e., has he provided accurate information to the

police a number of times in the past? If the informant's track record is

inadequate, it may be possible to satisfy the veracity prong by showing that the

accusation was a declaration against the informant's penal interest.

To satisfy the “basis of knowledge” prong, the informant must declare that he

personally has seen the facts asserted and is passing on first-hand

information. If the informant's information is hearsay, the basis of knowledge

prong can be satisfied if there is sufficient information so that the hearsay

establishes basis of knowledge.

State v. Jackson, 102 Wn.2d 432, 437-38 (1984) (citations omitted).

A conclusory statement, which presents no underlying facts from which the

issuing judicial officer could independently determine the informant's

reliability, is insufficient. Thus, the description “ ‘[a] reliable informant

who has proven to be reliable in the past’ ” was held insufficient . . . ."

State v. Colin, 61 Wn.App 111, 113 (1991).

Note: If the informant's tip fails under either or both of the two prongs of

Aguilar–Spinelli, probable cause may yet be established by independent police

investigatory work that corroborates the tip to such an extent that it supports

the missing elements of the Aguilar–Spinelli test. State v. Kennedy, 72 Wn.App

244, 250 (1993).

|

|

|

c. Does the warrant application fail to inlucde the criminal history of

the informants?

|

|

|

A known informant's criminal history of conviction for crimes of dishonesty,

should be included in the affidavit. U.S. v. Elliiot, 322 F.3d 710 (9th Cir.

2003). When an informant's criminal history includes crimes of dishonesty

additional evidence mut be included in the affidavit to bolster credibility or

the reliability of the tip. Without such bolstering information the informant's

criminal past involving dishonesty is fatal to the reliability of the

informant's information, and such information cannot alone support probable

cause. See id. at 716.

|

|

|

d. Are there Franks issues

with the warrant application?

|

|

|

A criminal defendant

may challenge a facially sufficient affidavit by showing it contains intentional

or deliberate falsehoods, or statements made with reckless disregard for the

truth. Franks v. Delaware,

438 U.S. 154, 171, 98 S.Ct. 2674

(1978).

The validity of a search warrant must be

assessed on the basis of information that officers disclosed as well as

information that they had a duty to disclose.

Maryland v. Garrison,

480 U.S. 79, 85, 107 S.Ct. 1013 (1987).

Police officers have

a duty to reveal “serious doubts” about an informant's testimony.

Molina ex rel. Molina v. Cooper, 325 F.3d 963 (7th Cir. 2003).

|

|

|

e. Did the officers discover information negating probable cause after

obtaining the warrant but before executing it?

|

|

|

When law enforcement received information after issuance of search warrant but

before its execution, which negated probable cause, officers were required to

return to magistrate for reevaluation of probable cause. State v.

Maddox, 152 Wn.2d 499, 508 (2004) but see

State v. Chenoweth,

160 Wn.2d 454, (2007)

(Negligent mistatements or ommisions do not invalidate warrant).

|

|

|

f. Does the application rely on illegally obtained evidence?

|

|

|

Illegally obtained evidence must be excluded from probable cause

determination. State v. Eisfeldt, 163 Wn.2d 628, 636 (2008).

|

|

|

g. Are the statements in support of probable cause merely the

applicant's conclusions?

|

|

|

The judicial officer must be given sufficient facts, not mere

conclusions, in order to perform his “ ‘neutral and detached’ function and not

serve merely as a rubber stamp for the police.”

State

v. Woodall, 100 Wn.2d 74, 77 (1983).

Negligent or

innocent misstatements will be excised if they are of a conclusory nature

unsupported by sufficient underlying facts to inform the magistrate of the basis

for the affiant’s conclusion. State v. Stephens, 37 Wn. App. 76, 79 (1984). See also State v. Taylor, 74 Wn.App.111, 122 n.7 (1994),

stating that it is not sufficient to

simply assert the standard controlled buy scenario was followed.

|